The Impact of Ancient Plant Medicine Trade on Global History

Faust

The ancient plant medicine trade shaped the course of human history, weaving a complex tapestry of cultural exchange, economic growth, and medical advancement across continents. For millennia, humans have turned to plants for healing, drawing on their potent properties to treat ailments, enhance rituals, and foster well-being. As civilizations grew and trade routes expanded, these botanical treasures became prized commodities, traversing vast distances along networks like the Silk Road, the Incense Route, and maritime pathways.

This intricate trade not only spread medicinal knowledge but also influenced economies, religions, and societal structures, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to resonate in modern pharmacology and cultural practices.

The Dawn of Plant Medicine in Human Societies

Long before written records, humans observed the natural world to discover plants with healing properties. Archaeological evidence suggests that as early as 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals used plants like yarrow and mallow, found in burial sites, possibly for medicinal or ritual purposes. In South Africa, traces of castor plant wax on tools from 24,000 years ago hint at sophisticated herbal techniques. These early practices laid the foundation for the ancient plant medicine trade, as communities began sharing knowledge and resources.

As human societies transitioned from nomadic to settled lifestyles during the Neolithic period, the cultivation and exchange of medicinal plants became more structured. Settlements like Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey stored large quantities of mustard seeds, suggesting early trade intentions. The domestication of plants such as opium poppy in Mesopotamia and aloe in Egypt marked a shift toward intentional cultivation, setting the stage for these botanicals to become valuable trade goods.

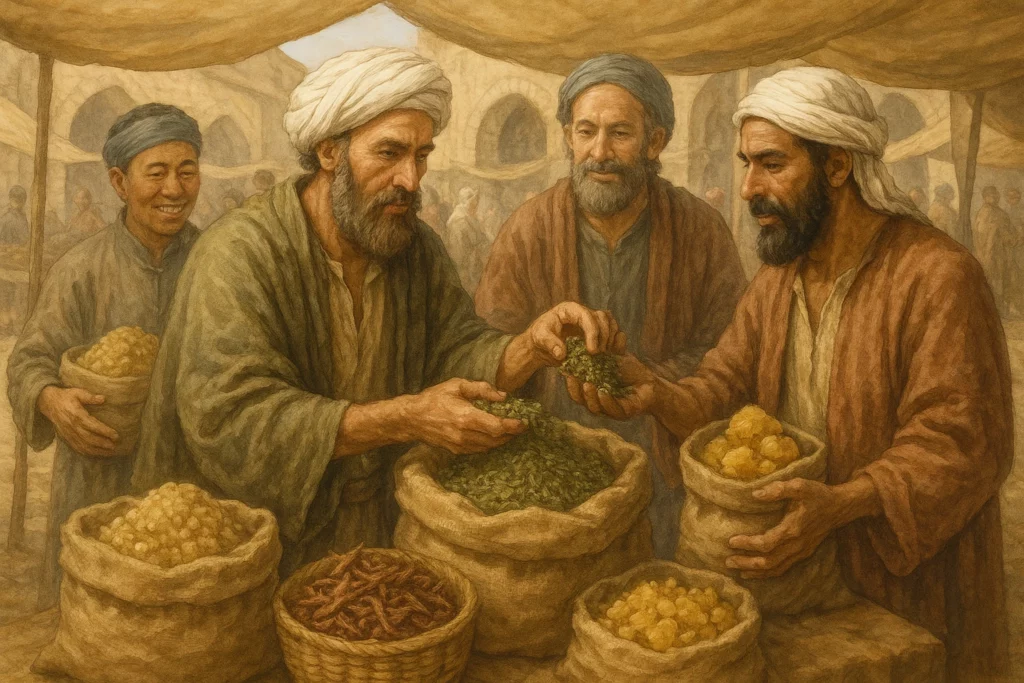

The Silk Road: A Highway for Healing Herbs

The Silk Road, a sprawling network of trade routes connecting East Asia to Europe, was a cornerstone of the ancient plant medicine trade. Spanning over 6,000 miles, this route facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures from the 2nd century BCE onward. Medicinal herbs were among the most coveted items, valued for their rarity and therapeutic potential.

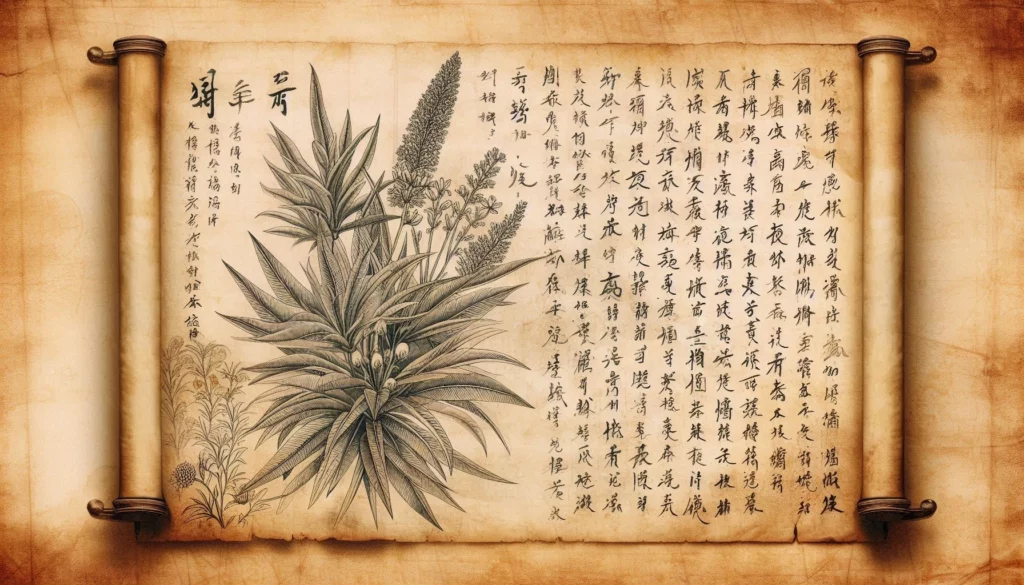

Chinese Contributions to Global Herbal Knowledge

In ancient China, herbal medicine was a cornerstone of healing practices, documented in texts like the Shennong Ben Cao Jing, attributed to the mythical emperor Shennong around 2700 BCE. This pharmacopoeia listed 365 medicinal plants, including ginseng, ephedra, and licorice, detailing their uses for ailments ranging from respiratory issues to digestive disorders. As Chinese merchants traveled westward, they carried these herbs, introducing them to Central Asia and beyond.

Ginseng, revered for its energizing properties, became a prized commodity in markets as far as Persia and Rome. Its trade not only enriched merchants but also spread knowledge of Chinese medical practices, influencing Persian and Greco-Roman traditions. Similarly, rhubarb, used as a laxative, found its way to Europe, where it was later celebrated in medieval apothecaries.

Persian and Indian Influences

Persia, a vital hub on the Silk Road, played a pivotal role in the ancient plant medicine trade. Persian traders introduced herbs like saffron, used for its mood-enhancing and anti-inflammatory properties, to China and India. The Compendium of Materia Medica by Li Shizhen, published in the 16th century, lists 46 medicinal plants from Persia, including frankincense and myrrh, which were integrated into Chinese medicine.

India’s Ayurvedic tradition, dating back to 2000 BCE, contributed significantly to the trade. Texts like the Charaka Samhita documented over 300 medicinal plants, such as turmeric and ashwagandha, used for their anti-inflammatory and adaptogenic effects. Indian merchants traded these herbs along the Silk Road, reaching the Middle East and Mediterranean, where they influenced Greek and Roman pharmacopeias. The exchange of turmeric, for instance, introduced its vibrant healing properties to distant cultures, shaping culinary and medicinal practices.

The Incense Route: Myrrh and Frankincense as Trade Pillars

The Incense Route, stretching from the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean, was another critical artery for the ancient plant medicine trade. Myrrh and frankincense, resinous gifts of the Commiphora and Boswellia trees, were among the most sought-after commodities, valued as much for their medicinal properties as for their use in religious rituals.

The Wealth of Southern Arabia

In ancient times, the kingdoms of southern Arabia, particularly Saba (modern-day Yemen), thrived on the trade of myrrh and frankincense. These resins were used to treat wounds, reduce inflammation, and aid digestion, as noted in the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus from 1550 BCE. Caravans laden with these precious substances traveled through harsh deserts to reach Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, commanding prices higher than gold.

Queen Hatshepsut’s expedition to the land of Punt around 1470 BCE exemplifies the lengths to which rulers went to secure these botanicals. Her voyage brought back myrrh trees to cultivate in Egypt, highlighting the strategic importance of controlling the supply of medicinal plants. This trade fostered diplomatic ties and cultural exchanges, as Egyptian medical knowledge blended with Arabian practices.

Mediterranean Connections

The Incense Route connected with Mediterranean ports, spreading myrrh and frankincense to Greece and Rome. Greek physician Hippocrates, known as the “Father of Medicine,” referenced these resins in his treatments for respiratory and skin conditions. Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia, documented their use in salves and incense, underscoring their role in both medicine and ritual. The trade of these resins enriched port cities like Alexandria, which became hubs of pharmacological innovation.

Maritime Routes: Spreading Plant Medicines Across Oceans

While land-based routes like the Silk Road and Incense Route were vital, maritime trade expanded the reach of the ancient plant medicine trade. From the 1st century CE, ships sailed from the Red Sea to India, Southeast Asia, and East Africa, carrying herbs and spices that transformed medical practices across regions.

The Indian Ocean Trade Network

The Indian Ocean trade network linked East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, India, and Southeast Asia, facilitating the exchange of medicinal plants like cinnamon, pepper, and cloves. Cinnamon, native to Sri Lanka, was valued for its antimicrobial properties and traded as far as Rome, where it was used in remedies for digestive issues. Pepper, known as “black gold,” was a staple in Ayurvedic and Greco-Roman medicine, used to stimulate digestion and treat fevers.

East African ports like Rhapta (modern-day Tanzania) exported aloe, which was prized for its soothing effects on burns and wounds. The Ebers Papyrus and Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica both praise aloe’s healing properties, reflecting its widespread use. These maritime exchanges introduced African plants to Asian and Mediterranean markets, enriching global pharmacopeias.

Southeast Asian Contributions

Southeast Asia contributed valuable spices like cloves and nutmeg, which were used medicinally for their antiseptic and analgesic properties. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a 1st-century CE Greek text, details the trade of these spices from the Moluccas to India and Rome. Cloves, for instance, were chewed to relieve tooth pain and used in ointments, influencing medical practices across cultures.

Cultural and Economic Impacts of the Plant Medicine Trade

The ancient plant medicine trade was more than a commercial enterprise; it was a catalyst for cultural and economic transformation. As plants crossed borders, they carried with them knowledge, beliefs, and practices, shaping the development of medical systems and societal structures.

Cultural Exchange and Medical Syncretism

The movement of medicinal plants fostered a blending of medical traditions. In the Mediterranean, Greek physicians like Dioscorides incorporated Egyptian and Persian herbs into their practices, creating a syncretic approach that influenced European medicine for centuries. His De Materia Medica, written around 60 CE, cataloged over 600 plants, including imports like cardamom and pepper, and remained a cornerstone of herbal knowledge until the Renaissance.

In Asia, the exchange of herbs along the Silk Road led to the integration of Indian Ayurvedic principles into Chinese medicine. For example, the use of sandalwood, traded from India, became prominent in Chinese rituals and remedies for its calming effects. This cross-pollination of ideas enriched medical texts and practices, creating a shared heritage of healing knowledge.

Economic Prosperity and Power Dynamics

The trade in medicinal plants fueled economic growth and shaped power dynamics. Cities like Petra and Palmyra thrived as trade hubs, their wealth derived from taxing caravans carrying myrrh, frankincense, and other botanicals. In China, the demand for ginseng and rhubarb drove the expansion of trade networks, enriching merchants and strengthening dynastic economies.

However, the high value of these plants also led to competition and conflict. The extinction of silphium, a North African plant prized for its contraceptive and medicinal properties, illustrates the risks of overharvesting. By the 1st century CE, sil Liberty was so heavily traded that it vanished, underscoring the need for sustainable practices—a lesson that resonates today.

The Role of Knowledge Transmission in the Plant Medicine Trade

The ancient plant medicine trade was not just about physical goods; it was a conduit for knowledge. Traders, healers, and scholars exchanged recipes, preparation methods, and philosophical approaches to healing, preserving and expanding herbal wisdom.

Written Records and Oral Traditions

Ancient texts played a crucial role in documenting plant medicines. The Egyptian Ebers Papyrus listed over 700 plant-based remedies, from garlic for strength to cannabis for pain relief. In India, the Atharvaveda and Sushruta Samhita detailed complex herbal formulas, while China’s Shennong Ben Cao Jing provided meticulous descriptions of plant properties. These texts were often translated and shared along trade routes, spreading knowledge across cultures.

Oral traditions were equally important, particularly among indigenous groups. In the Americas, Native American healers passed down knowledge of plants like echinacea and tobacco, which later influenced European settlers. Similarly, African shamans shared herbal wisdom through storytelling, some of which reached Asia via maritime trade.

The Role of Healers and Traders

Healers and traders were key figures in the ancient plant medicine trade. Druids in Celtic Europe, known for their deep knowledge of plants like mistletoe, influenced herbal practices in Britain and Gaul. In China, Taoist physicians traveled with merchants, sharing remedies like astragalus for immunity. These individuals acted as cultural bridges, ensuring that medicinal knowledge transcended geographical boundaries.

FAQ

Q: What made medicinal plants so valuable in ancient trade?

A: Medicinal plants were prized for their ability to heal, their rarity, and their cultural significance. Plants like myrrh, ginseng, and saffron were difficult to cultivate or harvest, making them scarce and expensive. Their use in medicine, rituals, and even as status symbols drove demand, often fetching prices higher than precious metals.

Q: How did ancient trade routes influence the spread of medical knowledge?

A: Trade routes like the Silk Road and Incense Route facilitated the exchange of herbal remedies and medical texts. Merchants and healers shared knowledge across regions, blending traditions like Ayurveda with Chinese and Greco-Roman practices, creating a rich, syncretic medical heritage.

Q: Which ancient civilizations were most involved in the plant medicine trade?

A: Civilizations like China, India, Egypt, Persia, and Rome were heavily involved. China exported ginseng and rhubarb, India traded turmeric and ashwagandha, Egypt and Arabia supplied myrrh and frankincense, while Rome and Greece integrated these into their pharmacopeias.

Q: Were there any downsides to the ancient plant medicine trade?

A: Yes, challenges included overharvesting, which led to the extinction of plants like silphium, and adulteration, where inferior substitutes were sold. Harsh trade conditions, banditry, and political conflicts also posed risks to merchants and the supply chain.

Q: How do ancient plant medicines influence modern pharmacology?

A: Many modern drugs have roots in ancient plant medicines. For example, aspirin is derived from willow bark, and artemisinin, used to treat malaria, comes from sweet wormwood, both of which were traded along ancient routes. These plants continue to inspire pharmaceutical research.

Q: Did the ancient plant medicine trade impact cultures beyond medicine?

A: Absolutely. The trade shaped economies by enriching trade hubs like Petra and Alexandria, influenced religious practices through the use of resins like frankincense, and fostered cultural exchanges that blended culinary, spiritual, and medical traditions across continents.

Conclusion

The ancient plant medicine trade was a vibrant force that connected civilizations, enriched economies, and advanced human health. From the Silk Road’s ginseng to the Incense Route’s myrrh, these botanicals carried not just healing properties but also stories of human resilience and ingenuity. By tracing their journeys, we gain a deeper appreciation for the shared heritage of medicine and the enduring power of plants. As we navigate modern challenges, the legacy of this trade reminds us to approach nature with reverence, curiosity, and a commitment to sustainability.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this blog of the ancient plant medicine trade is intended for educational and historical purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While ancient civilizations utilized various plants for medicinal purposes, the safety, efficacy, and appropriate use of these plants in modern contexts have not been universally validated by contemporary medical standards.

Many plants discussed, such as myrrh, ginseng, or opium poppy, may have potential health risks, side effects, or interactions with medications if used improperly. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional before using any herbal remedies or supplements, especially if you are pregnant, nursing, have pre-existing medical conditions, or are taking other medications.

The historical practices described do not reflect current medical guidelines, and some plants may be toxic or illegal in certain jurisdictions. Additionally, the cultivation, trade, or use of certain plants may be subject to legal restrictions or environmental regulations. The author and publisher are not responsible for any adverse effects or consequences resulting from the use of the information provided in this content. For accurate and safe medical guidance, seek advice from licensed healthcare providers.